End-User: A Guide to Sarrita Hunn’s Fuzzy Logic

by James McAnally

Version:1.0 StartHTML:0000000167 EndHTML:0000005610 StartFragment:0000000588 EndFragment:0000005594

Geometry has found its creative capacity reduced to variations of a grid.[1] The measurements of earth, the relative positions of one user and another, the properties of space. We prefer to mete them out in pre-established patterns. The gallery cube is filled with canvases, photos, plinths and frames, repeated in patterns and placed according to an ordered template. A poster, a postcard, a 2×2” advertisement in the newspaper has brought you here. Today, tonight, you the user are led out of the brick building onto square concrete blocks that add up to sidewalks. You follow instructions on the screen of your smartphone with icons arranged four columns over, four rows down, in order to look up at a predetermined distance towards a billboard—this particular rectangle depicting that modernist dream, an arch, framed, with the real curved steel just behind, blending into the billboard.

The proliferation of grids tells us of the expected end-users[2]: they are a mass, uniform in their tastes and qualities. Whatever differences exist between them are mediated by the format. The consistent presentation of information is paramount. An iPad, a laptop, a book, a billboard, a gallery—they present visual information and text within a general template, following a series of rules to make themselves comprehensible to the user. They are systems that exist for consistency and convenience of experience. Sketchbook, monitor, frame—they contain an idea within a grid, linking them with every other sketch, video, or painting that has ever followed the format.

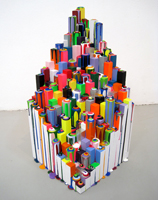

Throughout her career, Sarrita Hunn has consistently considered how templates and grids condition our ability to properly see, with the worlds of commercial printing and graphic design informing her multivaried approaches to painting. Taking the form of banners, sculpture, and video, but characteristically in dialogue with painting and information technology, her work has always multiplied out from pixels and rigid systems in increasing complexity. In her ambitious solo exhibition at Good Citizen in St. Louis, Hunn expands her work to an extreme conclusion, blurring together stock imagery, sculptural paintings, a series of commissioned augmented reality projects, cliché design conventions, and a growing curatorial approach to her own practice. The exhibition is brimming with ideas searching to see how real users use the system.[3]

Version:2.0 StartHTML:0000005611 EndHTML:0000009818 StartFragment:0000005595 EndFragment:0000008511

Stock imagery has always offered an affordable ability to recreate the feeling of a place without need of the actual place, and only emphasizes the fact that reality is utterly unnecessary for many applications—advertising, nostalgia, news, art. Art, in particular, has a long history of editing reality: expanding and limiting what we see for effect, testing what happens to us when we attempt to return to what we know, of course, is reality. Art is both more and less than reality. We know this, even if our eyes don’t.

On the billboard above Good Citizen gallery, Hunn has placed a refracted stock image of the Gateway Arch, that shorthand icon of St. Louis, so that at certain locations, the billboard and arch meet in such a way that they form a single, continuous symbol. It is a kind of magic trick, a stunning intervention causing the tallest monument in North America to disappear from the skyline, not by an errant aircraft, but instead by a well-placed advertisement gone wrong.

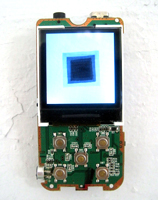

The billboard is an outgrowth of the artist’s interest in augmented reality technology that allows information to be added as a layer on top of our experienced reality. Augmented reality should perhaps here be replaced with its ambiguous synonym, mediated reality, which reflects our everyday lived environment in its totality. Our experience is altered by an accumulation of devices continuously overlaying information wherever we look. Both body and canvas, billboard and monument are utterly changed, drifting from reality into an in-between state. Was something added or taken away? Our eye perceives a stream; it greedily absorbs all symbols. Our bodies evolve more slowly than our apparatuses, unable to keep up with demands or process the meaning of what we see. Is the icon lost or expanded?

A similar stock image of a pixelated forest lurks inside, with a loose grid of paint spilling out of it onto the floor. Self-referential, sculptural paintings hang opposite. There is geometry everywhere, a concrete referent to Hunn’s earlier explorations. A wall is covered in a monotonous Photoshop grid–did we lose a layer, or is this a new design altogether? Opposite is a blown-up photo of brick, mirroring the red brick wall it extends from. Outside, Jake Peterson, Gareth Spor, and Jesper Carlsen add in their own augmented reality projects to supplement Hunn’s explorations with space and user experience.[4] Nightmare City, in some formats, folded this essay into printed-out iPhone. In others, it drifts in pixels, streaming down your screen. Reality is greedy; it wants more than the grids we are offering it. We are busy adding information behind your eyelids. We drift, caught between media. You are the end-user; the gallery is the format.

[1] See: Geometry: (Ancient Greek: γεωμετρία; geo- “earth”, -metria “measurement”) is a branch of mathematics concerned with questions of shape, size, relative position of figures, and the properties of space.

[2] See: End-user: An end user is a person who uses a product. The term is based in the fields of economics and commerce. A product may be purchased by several intermediaries, who are not users, between the manufacturer and the end user, or be directly purchased by the end user as a consumer.

[3] See: Usability Testing: Usability testing is a technique used in user-centered interaction design to evaluate a product by testing it on users. Usability testing focuses on measuring a human-made product’s capacity to meet its intended purpose.

[4] See: User experience (UX): User experience (UX) is the way a person feels about using a product, system or service. User experience highlights the experiential, affective, meaningful and valuable aspects of human-computer interaction and product ownership, but it also includes a person’s perceptions of the practical aspects such as utility, ease of use and efficiency of the system. User experience is subjective in nature, because it is about an individual’s feelings and thoughts about the system. User experience is dynamic, because it changes over time as the circumstances change.

This essay was published in In This Corner of the Holodeck, We Mine for Pure Powder Pigment–In This Corner of the Holodeck, We Mine for Pure Liquid Chrystal, an exhibition catalog/poster and website by Nightmare City for Fuzzy Logic at Good Citizen Gallery, St. Louis, MO (July 2012) and online at http://nightmarecity.org/FUZZY-LOGIC.